CHAPTER 7

Economic Growth: Malthus and Solow

KEY IDEAS IN THIS CHAPTER

4. End-of-chapter problems have been added.

Chapter 7: Economic Growth: Malthus and Solow

TEACHING GOALS

Students easily take for granted the much more abundant standard of living of today as

opposed to twenty, fifty, or one hundred years ago. Sometimes it is easier to remind

students of what their ancestors had to do without, rather than simply referring to per

capita income levels over time. Recessions come and go, and yet economic growth

swamps the lost output we endure during hard times. The most recent recession is unlike

the Great Depression, in that the drop in GDP below trend is not as large and is not as

prolonged, and our times are certainly not at all like the Great Depression in that our

incomes are many times larger than those of the typical person in Canada in the 1930s.

The typical student begins the study of economic growth against the backdrop of the

recent growth experience of Canada. The current standard of living in Canada vastly

surpasses the current standard of living in most countries and would have been

unimaginable anywhere in the world before the advent of the Industrial Revolution. Until

about 1800, the world economy produced little more than a subsistence level of income

for any but the richest individuals. Growth in per capita income was nonexistent. The

Malthusian model of growth explains the tendency of increases in population to dilute

any gains in productivity.

The Industrial Revolution introduced the possibility of sustained growth in per capita

income through the accumulation of physical capital. However, growth experience has

varied widely around the world. The richer countries have a sustained record of growth.

Since 1870, per capita income in Canada has been growing at an average rate of about

two percent per year. While two percent growth may seem small, it is important for

students to realize that such growth transforms into a more than doubling of per capita

GDP per generation. Unfortunately, the poorer countries have remained poor.

Furthermore, their growth rates have not generally matched growth rates in the richer

countries, so that the poor countries fall farther and farther behind. Such differences in

standards of living and growth prospects present puzzles that the study of economic

growth hopes to solve.

CLASSROOM DISCUSSION TOPICS

Getting students to relate to differences in standards of living can sometimes be difficult.

It is easy to take one’s own standard of living for granted. An interesting discussion topic

is whether students would be willing to travel back in time to 100 or 200 years ago, if

they could be one of the richest people of those earlier times. Would the trade-off be

worthwhile? While students typically stress factors like antiquated views about freedom

of choice and racial and gender issues, try to encourage students to direct their concerns

to those that are more economic than social. Also point out that higher standards of living

allow societies to be more concerned about issues of equality when mere survival is no

longer precarious.

Instructor’s Manual for Macroeconomics, Fourth Canadian Edition

Students often view population growth as the result of cultural factors and personal

preferences. Against the abundance of daily living, it is easy to forget economic factors.

Ask the students for examples of economic factors that might influence fertility decisions.

The Malthusian model suggests that growth may only be achieved through population

control. In the modern economy, the costs of raising children can be formidable, and so

there is a tendency for such costs to be a disincentive to fertility. Such costs may

contribute to the tendency for low fertility rates in advanced economies. In less developed

societies, having a large family can be a private form of social security. The more

children a family has, the more children there will be to provide for the parents in old age.

Poor public health conditions may actually enhance fertility. If each child has a smaller

chance for survival to adulthood, more births are required to produce a given-sized

family.

A major goal of most countries is to have sustained growth in per capita real GDP. Ask

students whether this is an appropriate goal for all countries in all periods. Is growth

always beneficial? What problems can growth bring?

Although growth normally leads to more jobs and a greater availability of goods and

services, growth can bring difficulties as well as gains. Rapid growth can cause

congestion and unhealthy living and working situations. The need for raw materials may

despoil pristine natural settings. In the lower mainland of British Columbia, the pressure

of economic and population growth has seriously reduced air quality and damaged

natural habitats for wildlife. Industrial production may pollute the air, water, and land. At

some point one must wonder if the price we pay for more goods and services is worth

what we give up in beauty and cleanliness.

1. Economic Growth Facts

a) Pre-1800: Constant per Capita Income across Time and Space

b) Post-1800: Sustained Growth in the Rich Countries

c) High Investment ↔ High Standard of Living

Chapter 7: Economic Growth: Malthus and Solow

2. The Malthusian Model

3. Solow’s Model of Exogenous Growth

a) The Representative Consumer

b) The Representative Firm

c) Competitive Equilibrium

4. Growth Accounting

a) Solow Residuals

b) The Productivity Slowdown

1. The amount of land increases and, at first, the size of the population is unchanged.

Therefore, consumption per worker increases. However, the increase in consumption

Instructor’s Manual for Macroeconomics, Fourth Canadian Edition

2. A reduction in the death rate increases the number of survivors from the current

period who will still be living in the future. Therefore, such a technological change in

public health shifts the function ()

g

c upward. In Problem 1 there were no effects on

the levels of land per worker and consumption per worker. In this case, the ()

g

c

Chapter 7: Economic Growth: Malthus and Solow

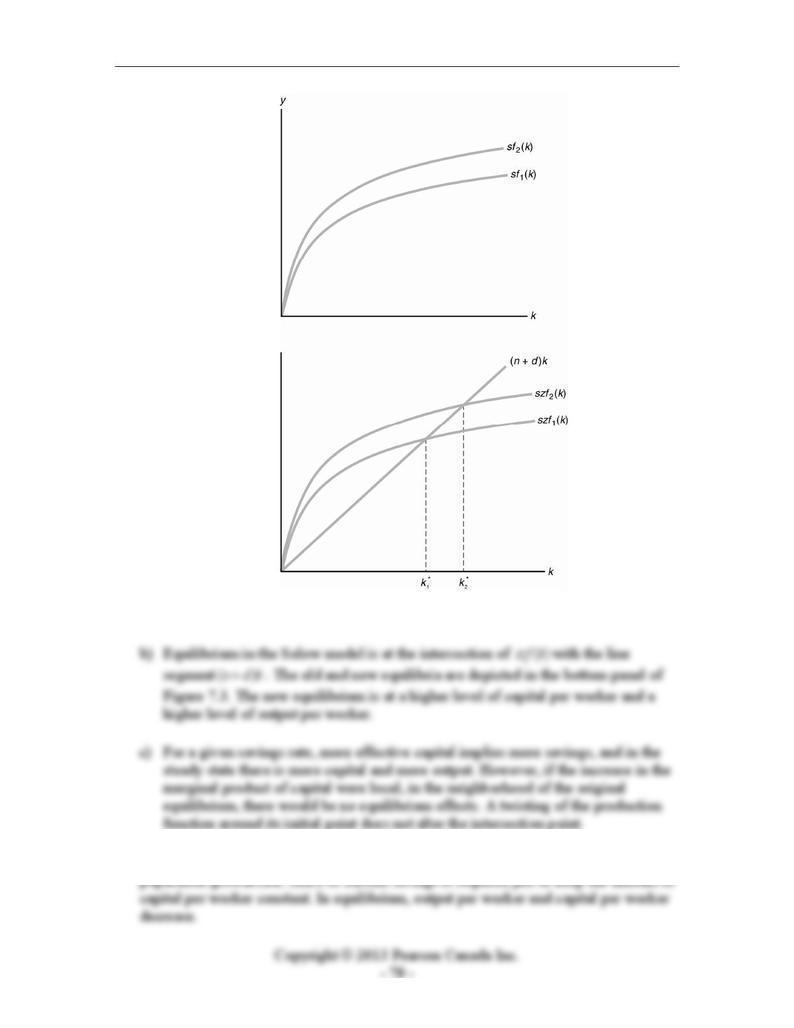

3. For the marginal product of capital to increase at every level of capital, the shift in the

production function is equivalent to an increase in total factor productivity.

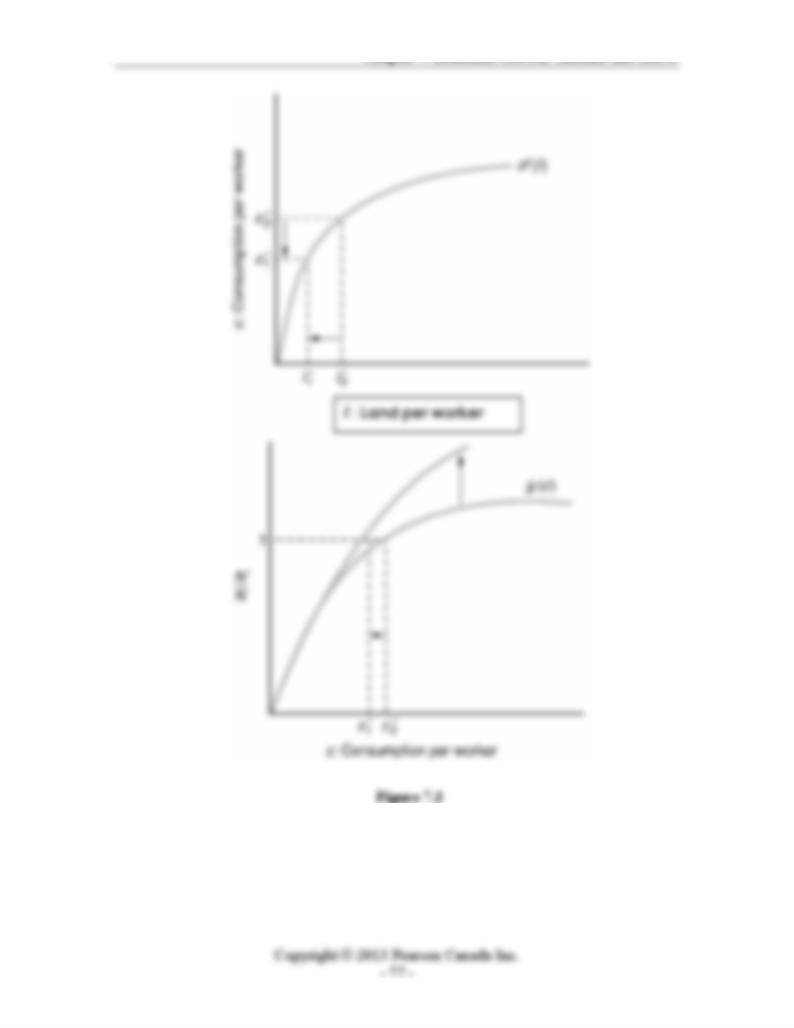

a) The original and new production functions are shown in Figure 7.3 below.

Instructor’s Manual for Macroeconomics, Fourth Canadian Edition

Figure 7.3

4. An increase in the depreciation rate acts in much the same way as an increase in the

Chapter 7: Economic Growth: Malthus and Solow

5. Destruction of capital.

a) The long-run equilibrium is not changed by an alteration of the initial conditions.

If the economy started in a steady state, the economy will return to the same

6. A reduction in total factor productivity reduces the marginal product of capital. The

Golden Rule level of capital per worker equates the marginal product of capital with

,11.02.0 5.0 kk =

Instructor’s Manual for Macroeconomics, Fourth Canadian Edition

k = 13.22, y = 3.64, and c = 2.18. Note that after 10 periods, the economy is much

8. Government spending in the Solow model.

'(1 ) (1 ) (1 )

s

knn n

=−+

++ +

Chapter 7: Economic Growth: Malthus and Solow

Setting k = k’ we find that:

9. The Golden Rule quantity of capital per worker *

k is such that *

()

M

Pzfk nd

′

==+. A

Instructor’s Manual for Macroeconomics, Fourth Canadian Edition

10. a) Capital evolves over time, as in Equation 7.16, according to

KdbNKszFK )1(),(' −+= .

Now, simplifying, as for Equation 7.17, we get

kdkszffnk )1()()1)(1(' −+=++ ,

where k is now the quantity of capital per efficiency unit of labour, and f(k) is the

11. Production linear in capital:

'(1 )

s

kk

n

=

+.

'(1)

N

(1 )

n

+, per capita income grows indefinitely.

b) The growth rate of income per capita is therefore:

Chapter 7: Economic Growth: Malthus and Solow

(1 )

n

=

+

Obviously, g is increasing in s.

(7.19),

**

()( )szf k n d k=+ ,

*0.27savings investment sy===

We then start the economy in the first period in this steady state, and consider two

alternative scenarios. In the first (part b of the question), we consider a temporary

decrease in TFP, with z falling by 10% in period 2, then returning to its previous level

forever. In the second case (part c of the question), there is a permanent decrease of 10%

in TFP beginning in period 2. Since consumption and investment are proportional to

output, it will be sufficient just to show the path of output in the two cases. In Figure 7.6,

Instructor’s Manual for Macroeconomics, Fourth Canadian Edition

2010 1325 2668.7 17.04 17.0725

Chapter 7: Economic Growth: Malthus and Solow

2010 3.217263 2.343151 1.368233 1.532105