CHAPTER 17

Money, Banking, and Inflation

KEY IDEAS IN THIS CHAPTER

2. All charts and tables have been updated to reflect new data.

TEACHING GOALS

In the modern world, the use of money as a social contrivance is largely taken for

granted. Although study of the mechanisms of trading may seem rather arcane, it may

Chapter 17: Money, Banking, and Inflation

open some students’ minds to the value of adopting a uniform medium of exchange.

Students should fully understand that a world of rugged individualism in which everyone

is self-sufficient is the most likely alternative to a monetary economy.

The level of the money supply is neutral. The growth rate of the money supply has

allocative effects on the economy. Continuous growth in the money supply causes

inflation. Inflation erodes money’s usefulness as a medium of exchange. As inflation

worsens, households substitute non-market activities, which require no money, for market

activities that do require money. Therefore, as the inflation rate increases, output and

employment decrease.

Financial intermediation is an important topic for macroeconomists because of the role of

financial intermediaries in providing a medium of exchange, and because interactions

between central banks and financial intermediaries are an important component of the

money supply process. Financial intermediaries acquire illiquid assets in the form of

loans and transform these assets into more liquid assets preferred as media of exchange.

The Diamond-Dybvig model is a useful tool that demonstrates how banks might offer

insurance against an untimely need for liquidity. The Diamond-Dybvig model is also

useful in explaining bank runs and how government-provided deposit insurance may

prevent such runs.

CLASSROOM DISCUSSION TOPICS

An important tenet of monetary economics is the dominance of monetary economies over

economies without a commonly accepted medium of exchange. Yet we still find the

existence of barter clubs. These clubs sometimes arrange direct one-for-one trades

between individuals or businesses that have a double coincidence of wants. Sometimes

they arrange three-way transactions similar to those depicted in Figure 15.2 in the text.

Some of these clubs utilize credits that circulate as a private medium of exchange

between members. To find some examples, suggest a Google™ search on the term

“barter.” Ask if any student has heard of such arrangements or even participated in them.

Are the users of these services irrational? Does the existence of such organizations

suggest that monetary exchange is becoming outdated?

The widespread use of computer technology has lowered the information costs associated

with barter exchange. But such technology also reduces the cost of engaging in monetary

transactions. Marketing materials provided by these exchanges emphasize that they allow

businesses to buy necessary products and services without the need for cash. Does this

mean that barter exchange can combine credit exchanges with goods and services

exchanges? The marketing materials also promise a source of new business for members.

In a perfectly competitive world, there is no need to find more customers. Does this mean

that barter transactions are enhanced by the existence of monopolistic competition? The

clubs also suggest the importance of personal relationships between buyers and sellers. Is

this a solution to informational problems inherent in anonymous markets? In any event,

the total volume of transactions on such exchanges is a trivial percentage of all

Instructor’s Manual for Macroeconomics, Fourth Canadian Edition

transactions. It is not likely that the foundations of monetary theory will become outdated

in the near future.

Most of today’s students have not had any personal experience with significant inflation.

Ask students if they ever worry about inflation. There may be students from other

countries (Russia, Eastern Europe, the former Yugoslavia, etc.) who have experienced

high inflation. Can anyone imagine a set of circumstances that would lead to a serious

Canadian inflation problem? Would students find more inflation objectionable? Do the

problems that students ascribe to inflation conform to theory, or are they more a figment

of confusion between real and nominal variables?

1. Alternative Forms of Money

a) Commodity Money

3. A Growing Money Supply and the Effects of Long-Run Inflation

Chapter 17: Money, Banking, and Inflation

(2) Current Leisure-Consumption Choice: ,1

lC

w

MRS

R

=

+

b) A Change in the Growth Rate of the Money Supply

i) Output and Employment Effects

ii) The Friedman Rule

iii) Deflation

iv) Hyperinflation

c) Money Growth, Inflation, and Output Growth Across Countries (Macroeconomics

in Action 15.2)

5. The Diamond-Dybvig Model

Instructor’s Manual for Macroeconomics, Fourth Canadian Edition

6. Deposit Insurance

a) Bank Failures in the Great Depression

1. In this case, Type I traders would use the commodity money they produce (good 2) to

2. Consumes 1 Consumes 2 Consumes 3

Produces 3 Produces 1 Produces 2

3. Suppose that the central bank acquires K units of capital in the current period, and

issues M units of money to finance these purchases, so that

MK

=. (1)

'

'

P

= (3)

So, substituting in equation (2) using (1) and (3), and rearranging, gives

,

'

KP

rK K P

=− +

and solving, we obtain

Chapter 17: Money, Banking, and Inflation

4. The fact that inflation alters the real opportunity cost of holding money is the only

6. Asset characteristics.

i) Works of art typically have a low (financial) rate of return. The only source of a

return is appreciation in the market price. Works of art are quite risky and are

highly illiquid. The maturity of a work of art is zero because there are no future

financial payments. Works of art are stores of value, but not media of exchange or

units of account.

ii) U.S. Treasury Bills have a low rate of return in comparison to other financial

instruments. They are almost riskless due to the government’s ability to raise

taxes to pay principal and interest. They are short-maturity assets and are highly

liquid. Treasury Bills are a store of value. Technically, they are not a medium of

exchange, although their high liquidity warrants their inclusion in the L definition

of the money supply.

Instructor’s Manual for Macroeconomics, Fourth Canadian Edition

8. Production cannot be interrupted.

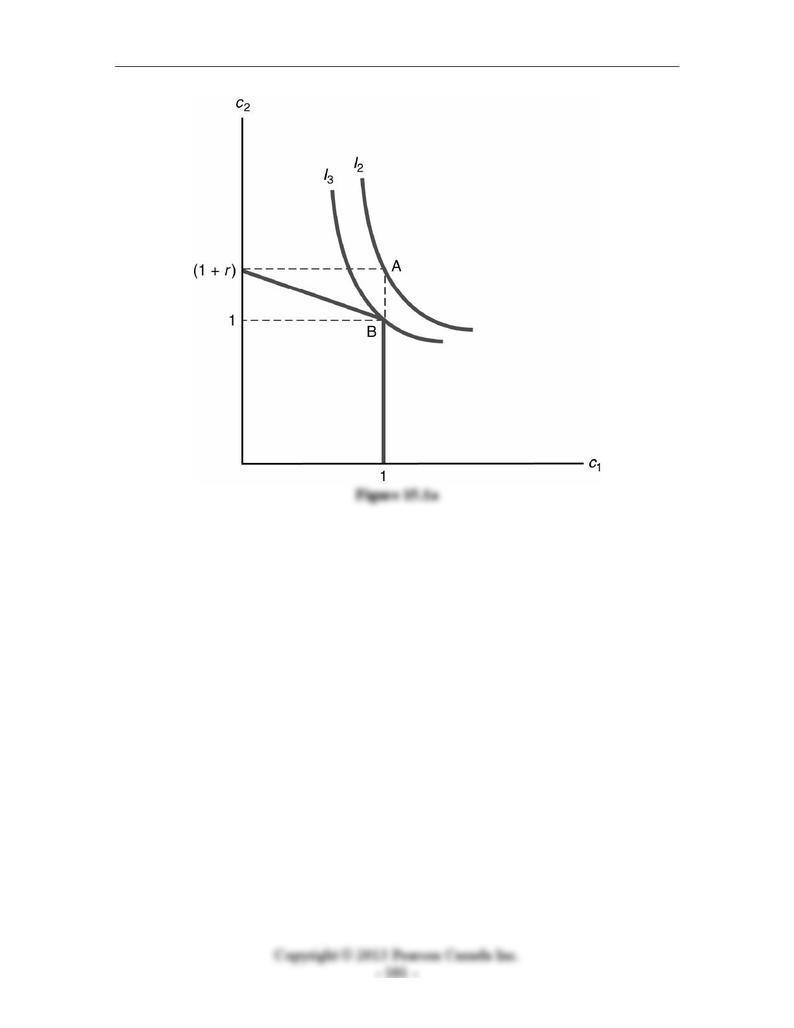

a) In the standard model, with no bank, the consumer has no reason not to commit

all of her resources to production. If the consumer turns out to be an early

consumer, production is interrupted and the consumer has 11c=. If the consumer

1(1 )crc=+ − . Now

superimpose the indifference curves; Figure 15.1a depicts optimization for the

consumer for interruptible and non-interruptible production. The figure depicts

the case of two corner solutions at points A and B. Point B corresponds to the no

interruption case with z = 0. The indifference curves would need to be

considerably flatter for the consumer to choose an interior solution for z. Clearly,

the consumer is worse off when production cannot be interrupted.

Chapter 17: Money, Banking, and Inflation

Instructor’s Manual for Macroeconomics, Fourth Canadian Edition

9. Each consumer will invest their entire endowment of 1 unit in the production

technology in period 0. In period 1, if an early consumer must choose the fraction of

the investment, x, to sell at the price p, and will interrupt the remaining fraction 1 – x

and consume it. The early consumer then chooses x to maximize pxx +−1, and the

solution is x = 0 if p < 1, x = 1 if p > 1, and the consumer is otherwise indifferent. In

Chapter 17: Money, Banking, and Inflation

10. Moral hazard problems.

a) The child is more likely to report having trouble because having trouble is

rewarded with help.