CHAPTER 13

Business Cycle Models with Flexible Prices and Wages

KEY IDEAS IN THIS CHAPTER

Instructor’s Manual for Macroeconomics, Fourth Canadian Edition

5. New end-of-chapter problems.

TEACHING GOALS

Chapter 3 demonstrated there are strong regularities associated with the comovements

among macroeconomic variables. Though business cycles are remarkably similar,

understanding their causes is a difficult task. There are multiple alternative business cycle

models, and students need to understand how these models are different – in terms of

what causes business cycles in these alternative models, and what the policy prescriptions

are. In need not be the case that we want to totally dismiss any business cycle models.

Potentially many models could give us useful insight what business cycles are about.

The models in this chapter are all based on flexible wages and prices. Sometimes these

are called “equilibrium” models, but even models with sticky wages and prices – for

example the New Keynesian model in Chapter 14 – have some notion of equilibrium. It is

important for students to understand, in spite of the fact that much of Keynesian

economics is done with sticky-wage-and-price models, that Keynesian ideas do not

depend on sticky wages and prices.

There are three elements in any business cycle model that are important: the impulses

(shocks), the propagation mechanism, and the policy conclusions. In the real business

cycle (RBC) model, the impulses are shocks to total factor productivity (TFP), these

shocks are propagated through the optimizing choices that are made by economic agents,

and in the baseline model there is no role for policy. In the Keynesian coordination

failure model the impulses are endogenous – self-confirming optimism and pessimism.

Propagation occurs in the same way as in the RBC model, but there may be a role for

government policy in improving matters. Either model fits the data as well as the other.

The last model in this chapter is a New Monetarist model, which is included to capture

specifically some features of the financial crisis, rather than as a general model of

business cycles. The novelty is the idea that financial liquidity is important in financial

crises, and that this requires a different way of thinking about monetary policy.

CLASSROOM DISCUSSION TOPICS

A key idea in this chapter is that a preliminary evaluation of a model’s usefulness

involves fitting the data. It would be good to discuss why this is valid. Might we imagine

models that did not fit the data well but might nevertheless be useful? Do we want the

model to fit all the data? Surely a model intended for the study of business cycles need

not give good predictions about the price of orange juice ten years from now.

Chapter 13: Business Cycle Models with Flexible Wages and Prices

Macroeconomists have been criticized for not foreseeing the financial crisis. Would that

have been feasible? Is forecasting all the macroeconomists do? Point out that an

important goal in macroeconomics is to design models that can be useful for policy

analysis.

Why should we study different business cycle models? Surely they cannot all be correct.

Discuss how policymakers use models to make policy decisions. The models need to be

simple. There can be many factors at work in the real world, but putting these all in one

model may just be confusing.

One could have a discussion about the recent financial crisis and recession, and what the

models in this chapter had to say about it. Possibly these approaches missed the boat in

1. The Real Business Cycle Model

(2) Central Banks and Price-Level Stabilization

(2) The Smoothing of Tax Distortions

Instructor’s Manual for Macroeconomics, Fourth Canadian Edition

2. A Keynesian Coordination Failure Model

a) The Workings of the Model

i) Coordination Failures

ii) Strategic Complementarities

iii) Multiple Equilibria

iv) Increasing Returns to Scale

b) The Coordination Failure Model: An Example

i) The Downward-Sloping Goods Supply Curve

3. A New Monetarist Model: Financial Crises and Deficient Liquidity

1. The effects in the goods and labor markets are identical to what we considered in

Chapter 11. Output increases, the real interest rate rises, consumption and investment

fall, employment rises, and the real wage falls. What we need to add to the Chapter 11

analysis are the effects in the money market. Since output increases and the real

Chapter 13: Business Cycle Models with Flexible Wages and Prices

2. We already know that permanent increases in total factor productivity are consistent

with all of the business cycle facts. As developed in the answer to problem 1, above,

11. Here, we need to add the effects in the money market. Since output increases

and the real interest rate increase, the net effect on money demand is ambiguous,

so the price level could rise or fall.

b) From Chapter 11, we know that this shock causes investment to increase, there is

4. If the money supply were the only variable that shifts the economy between the bad

and good states, the monetary authority would need to increase the money supply

5. This shock acts to shift the labor supply curve to the right which, when we construct

the output supply curve, implies a shift to the left in that curve. As well, because there

is an increase in the demand for consumption goods, the output demand curve shifts

to the right. As shown in Figure 13.1, output in the good equilibrium increases, and

the real interest rate is lower in the good equilibrium. Thus, in the good equilibrium,

6. The permanent increase in government spending does not affect the aggregate

demand curve, because the increase in government spending generates an

approximately equal decrease in consumption. The implied increase in taxes shifts the

labour supply curve to the right. In the coordination failure model, this produces a

leftward shift in aggregate supply. Recall that the labour demand curve is upward

sloping and steeper than the labour supply curve. A leftward shift in aggregate supply

is depicted in Figure 13.2, below.

In the “good” equilibrium, output increases and the real interest rate decreases. That

output increases requires that employment increase. The increase in employment

moves the economy along the labour demand curve, so that the real wage rate must

Chapter 13: Business Cycle Models with Flexible Wages and Prices

Instructor’s Manual for Macroeconomics, Fourth Canadian Edition

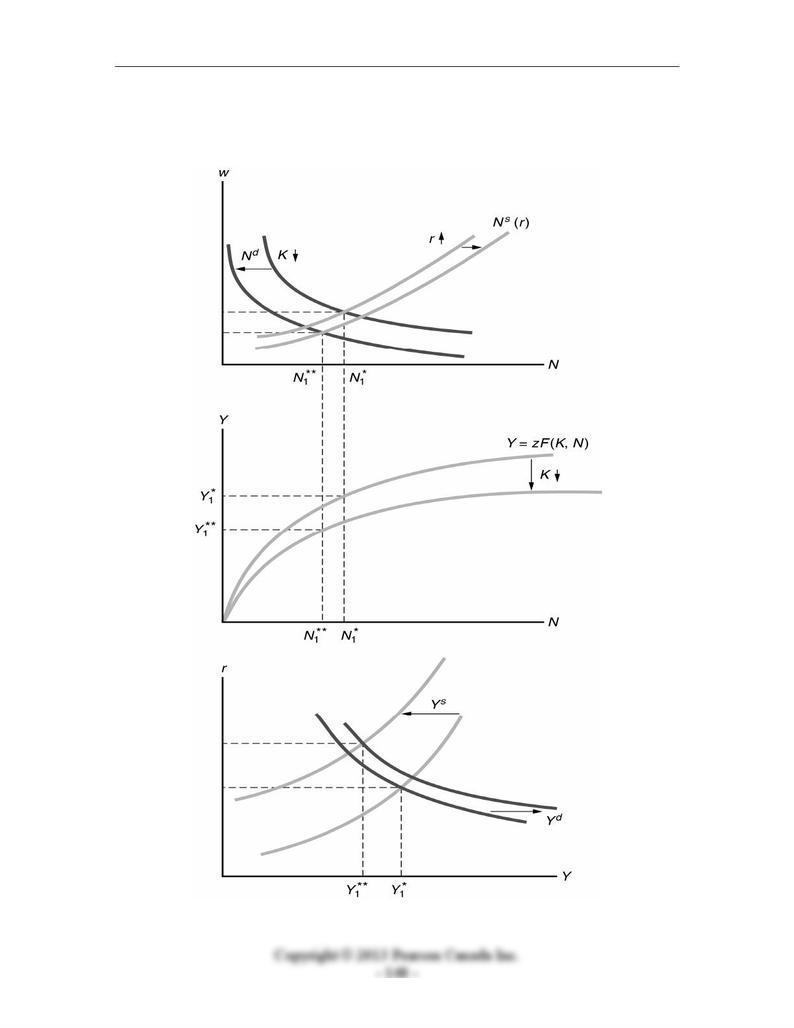

7. The effects of the decrease in the capital stock depend on the specific model we are

working with. The effect of the decrease in capital in the real business cycle is

depicted in Figure 13.3, below.

Figure 13.3

Chapter 13: Business Cycle Models with Flexible Wages and Prices

8. a) In the real business cycle model, what the central bank should do in response to a

decline in TFP depends on the central bank’s goals. If the central bank wishes to

stabilize the price level, then it should reduce the money supply, but money is

neutral in the real business cycle model, so there is no role for the central bank

other than price level control.

b) In the coordination failure model, money is neutral, just as in the real business

9. In the New Monetarist model, if there is deficient financial liquidity, then a tax cut

financed by an increase in the quantity of nominal government bonds, B, will increase

the quantity of liquid financial assets, a. This shifts the output demand curve to the

right, as in Figure 13.4, and the real interest rate and output both increase. This

Instructor’s Manual for Macroeconomics, Fourth Canadian Edition

11. If there is deficient financial liquidity, then quantitative easing – an increase in M

matched by a decrease in k(r) – gives the same effects as in Figure 13.16 in the