Chapter 7

Nontariff Barriers and Arguments

for Protection

This chapter continues our discussion of commercial policy. It first details various nontariff barriers to

trade that exist in today’s world. A major part of this discussion is devoted to quotas and other forms of

quantitative barriers such as voluntary export restraints (VERs). In addition, other forms of nontariff

barriers are discussed, largely by illustration. The second part of the chapter is devoted to exploring the

general validity of a number of common arguments for protection. Included in this material are several

examples of strategic trade policy.

We have found that the material in this chapter tends to be very popular with students. They are

especially interested in various examples of nontariff barriers, and Baldwin’s book remains an excellent

source for further illustrations of these policies. We also find it useful to challenge students to provide

arguments of their own for protection. Often, these arguments will be variants upon the invalid arguments

we discuss in the chapter. Classroom discussion devoted to sorting out valid from invalid arguments is

time well spent. For an additional example of the cost of U.S. VER agreements to American industries,

see The Effects of the Steel Voluntary Restraint Agreements on U.S. Steel-Consuming Industries,

U.S.I.T.C. publication #2182, May 1989. Robert Feenstra argues that estimates of the costs of U.S. quota

protection are understated if they ignore the efficiency costs these policies impose on foreign countries

(See “How Costly is Protectionism?” Journal of Economic Perspectives, summer 1992, pp. 159–178).

◼ Chapter Outline

Introduction

Quotas

The Welfare Effects of Quotas

The Equivalence or Nonequivalence of Tariffs and Quotas

Other Nontariff Barriers

Chapter 7 Nontariff Barriers and Arguments for Protection 31

1. In what ways are tariffs and quotas similar in their effects? In what ways do they differ?

2. Suppose that prospective importing firms hire lobbyists to help them secure from government

authorities the right to import quota-restricted items into a country. How much would importers as

a group be willing to pay lobbyists for their services? Explain. Suppose lobbyists are paid this

amount. What happens to domestic welfare in this case?

3. Suppose that a country requires special inspections on all imported food but it exempts domestic

production from similar inspection. What effect would this have on imports, domestic production,

prices, and quantity consumed? Explain fully.

4. Show graphically that a monopolist will charge a higher price and produce at a lower level of output

with quota protection than with a tariff protection that yields the same level of imports.

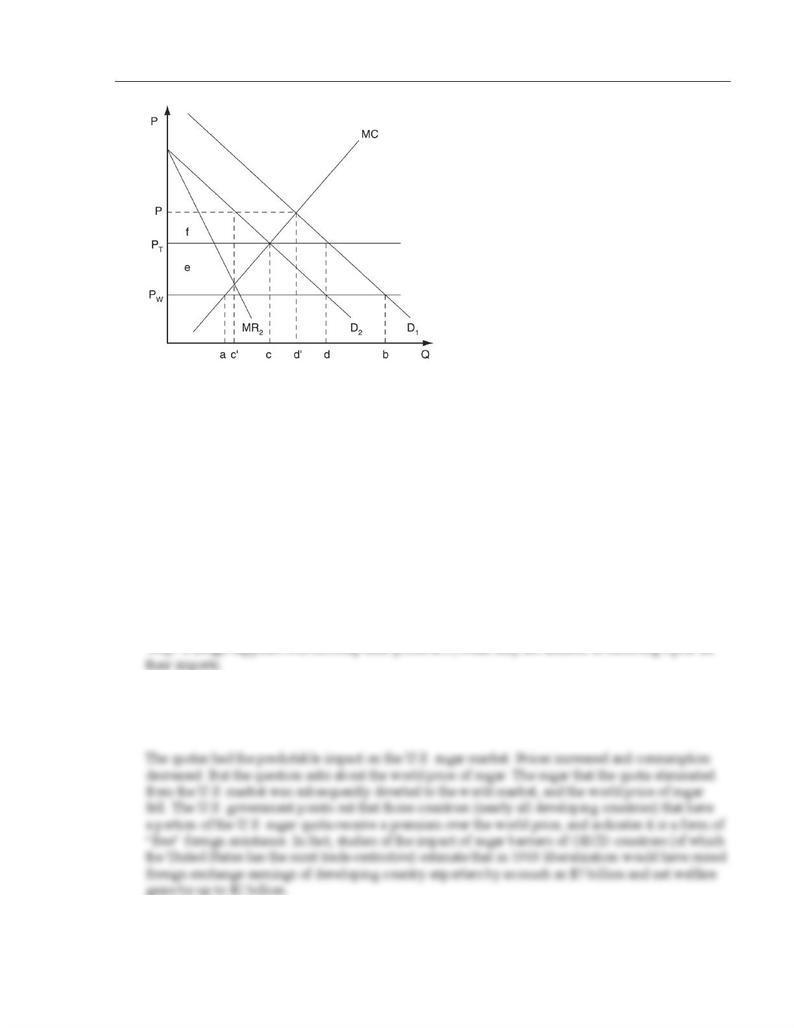

Suppose the market for this good is illustrated to the right. In this case, the domestic supply curve is

the marginal cost curve of just one firm (the monopolist) rather than the sum of all firms’ marginal

costs. In free trade at price Pw, imports would equal the amount ab and the domestic producer faces

a competitive market. Consider a tariff in the amount (Pt − Pw): The price would rise to Pt and

imports would decrease to cd. The domestic producer is still forced to behave competitively

(charging Pt) because the tariff simply adds to foreign producers’ costs.

Chapter 7 Nontariff Barriers and Arguments for Protection 33

Suppose the tariff was changed to a quota and imports were strictly limited to cd. The domestic

producer can now exercise his monopoly power. He knows that the market demand curve, D1, minus

imports under the quota, will be the demand curve facing his firm. Note that D2 parallels D1 with

the distance cd between them, and the marginal revenue curve drawn corresponding to the demand

curve D2. (You may need to go to an elementary microeconomics book and review the section on the

monopolist’s marginal revenue curve.) A profit-maximizing firm will choose to produce where

marginal revenue equals marginal cost, at output level oc, but can charge a price appropriate to his

demand curve. In this case, he can charge Pq. Note that at price Pq, domestic production oc and

imports cd will just satisfy demand.

Welfare changes aren’t certain without more information. In the movement from free trade to the

tariff, the government gained the tariff revenue and the monopolist gained all of $e above the supply

curve (plus the small triangle in the shaded area above the supply curve). When the tariff was

changed to a quota, the government lost the tariff revenue while the monopolist added all of $f to $e

(although it did lose the shaded triangle). If the quota rights were given to the foreign suppliers, then

they gained all the quota rent, which you should note is substantially larger than the tariff revenues.

5. The United States has used quotas to protect its domestic sugar industry. What has been the likely

impact of these quotas on the world price of sugar (relative to the price that would exist under free

trade)? Explain.

34 Husted/Melvin • International Economics, Ninth Edition

6. Is the optimum tariff argument a valid argument for protection? (Hint: See Chapter 6). Is it the best

policy for these purposes? Explain.

When a country has sufficient market power, it may be possible to impose an import tariff and

improve domestic welfare. This occurs because the country’s action affects the perceived demand

for the good on the world market and forces the importers to lower the world price. In this case, the

government gains tariff revenue while minimizing the deadweight loss—the optimal tariff maximizes

the sum of the two. (But what happens to world welfare? Is the welfare loss in the producing country

7. Consider the example of airplane building and strategic trade policy described in the text. Suppose

that the United States matched Europe’s export subsidy with a subsidy of 10 to Boeing. How would

this policy affect the solution to the game? What would be the welfare effects of this policy on the

United States and Europe?

8. The United States automakers have announced programs to build and market electric cars. Should the

U.S. impose temporary protection on this product to guarantee U.S. commercial success? Why or

why not?

9. Suppose that the domestic demand and supply for hats in a small open economy are given by

Q = 100 − P (demand)

Q = 50 + 2P (supply)

where Q denotes quantity and P denotes price.

a. If the world price is 10, what is the free trade level of imports?

b. Suppose that the country imposes a quota of 11 units. How much will the domestic price rise?

Chapter 7 Nontariff Barriers and Arguments for Protection 35

P = 13.

Thus price rises by 3.

c. & d. The welfare effects include the deadweight costs and (possibly) the quota rents.

10. According to the analysis in this chapter, VERs are a more costly form of protection than tariffs or

other types of quotas. Why do countries like the United States continue to protect certain industries

using this form of protection?

11. Suppose that Guatland protects its motorcycle industry with a quota that raises domestic prices by

$100 per unit. If Guatland’s government were to then impose a tariff of $90 per motorcycle, what

would happen to Guat motorcycle imports? What would be the welfare effects of this tariff on the

Guat economy?

12. Under what circumstances can commercial policy be an effective tool to solve world environmental

problems? Under what circumstances will commercial policy not be very effective? In general, which

set of circumstances is more likely to exist in the real world?