CASE 1.8

CRAZY EDDIE, INC.

Synopsis

Eddie Antar opened his first retail consumer electronics store in 1969 near Coney Island in New

York City. By 1987, Antar's firm, Crazy Eddie, Inc., was a public company with annual sales

exceeding $350 million. The rapid growth of the company's revenues and profits after it went public

in 1984 caused Crazy Eddie's stock to be labeled as a "can't miss" investment by prominent Wall

Street financial analysts. Unfortunately, the rags-to-riches story of Eddie Antar unraveled in the late

1980s following a hostile takeover of Crazy Eddie, Inc. After assuming control of the company, the

new owners discovered a massive overstatement of inventory that wiped out the cumulative profits

reported by the company since it went public in 1984. Subsequent investigations by various

regulatory authorities, including the SEC, resulted in numerous civil lawsuits and criminal

indictments being filed against Antar and his former associates.

Following the collapse of Crazy Eddie, Inc., in the late 1980s, regulatory authorities and the

business press criticized the company's auditors for failing to discover that the company's financial

statements had been grossly misstated. This case focuses on the accounting frauds allegedly

perpetrated by Antar and his associates and the related auditing issues. Among the topics addressed

by this case are the need for auditors to have a thorough understanding of their client's industry and

the importance of auditors maintaining a high level of skepticism when dealing with a client whose

management has an aggressive, growth-oriented philosophy. This case also clearly demonstrates the

need for auditors to consider weaknesses in a client's internal controls when planning the nature,

extent, and timing of year-end substantive tests.

57

Crazy Eddie, Inc.--Key Facts

10. Crazy Eddie's auditors allegedly failed to adequately consider several "red flags," including

6. To emphasize the importance of considering major weaknesses in a client's internal controls

when planning the nature, extent, and timing of year-end substantive tests.

Suggestions for Use

This case could easily be integrated with classroom coverage of analytical procedures. Crazy

Eddie's auditors were criticized by third parties for failing to investigate red flags in the company's

financial statements that resulted from Antar’s fraudulent schemes. The first case question requires

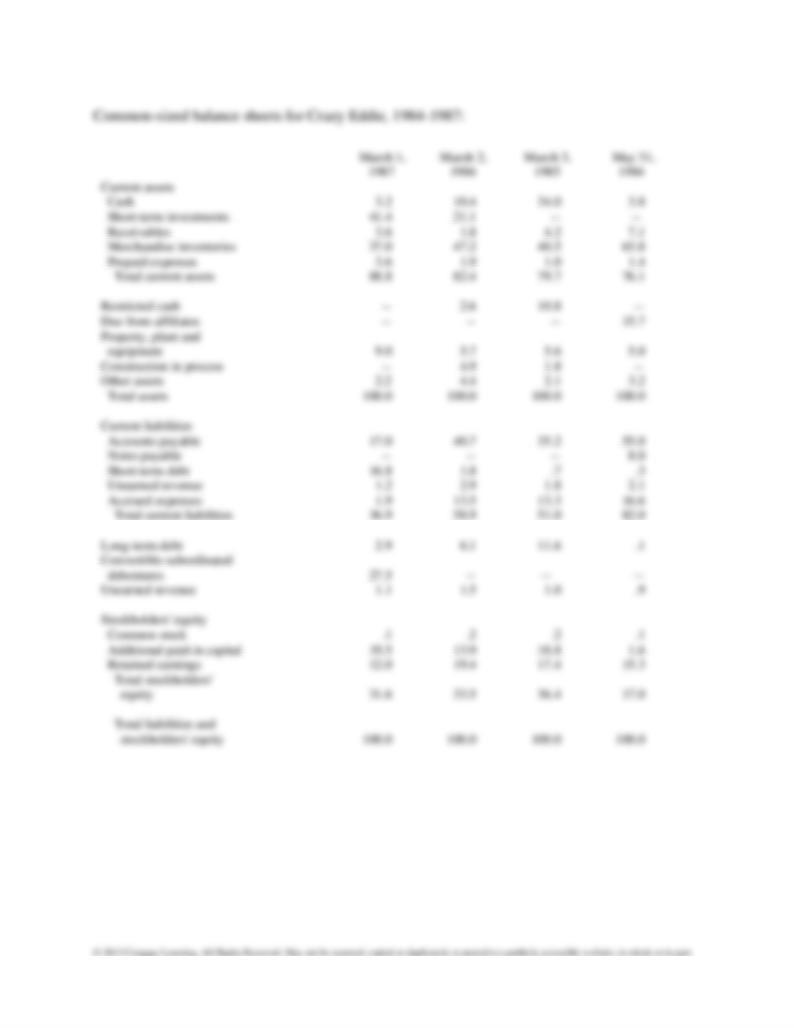

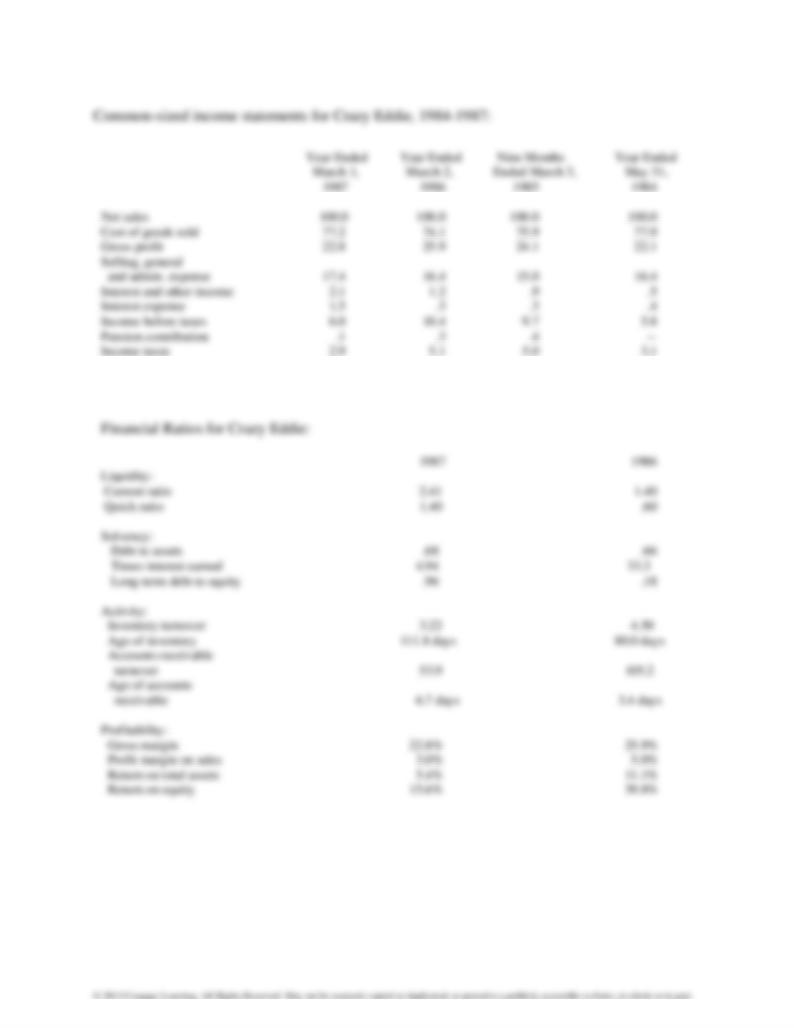

1. On the following pages are common-sized balance sheets and income statements for Crazy

Eddie's for the period 1984-1987. Additionally, key financial ratios for the company's 1986 and

1987 fiscal years are presented.

Clearly, Crazy Eddie's inventory account should have been, and almost certainly was, a focal

point of attention during the company’s 1984-1987 audits. Inventory is nearly always the key asset

of a retailer: no inventory, no sales . . . no company. In the case of Crazy Eddie's, the inventory

account dominated the company's periodic balance sheets. Granted, at the end of fiscal 1987,

inventory was only the second largest asset of the company but that was an anomaly due to the

company investing proceeds from sales of stock and convertible debentures into short-term

marketable securities.

Notice that Crazy Eddie's inventory increased dramatically over this time period, from $23

million in 1984 to nearly $110 million in 1987. Also notice that the company's inventory turnover

slowed considerably during 1987 resulting in the average age of inventory leaping from 80 days to

more than 111 days. When the age of a company's inventory increases significantly, the risk of

obsolescence and related valuation problems must be seriously considered by the firm's auditors.

Case 1.8 Crazy Eddie, Inc.

61

Case 1.8 Crazy Eddie, Inc.

62

Net income

3.0

5.0

4.3

2.7

1) Copy all inventory count or compilation sheets following completion of the physical

2) To reduce the likelihood of clients' recording bogus inventory items, auditors must also

2) Review the client's procedures for recording wholesale transactions to ensure that

proper controls exist for these transactions. Perform tests of controls to assess the

operating effectiveness of these controls.

d. Inclusion of consigned merchandise in year-end inventory:

When a client has merchandise in its retail outlets that is owned by third parties, the

3. AU Section 311, “Planning and Supervision,” notes that auditors should obtain “an

understanding of the entity and its environment” (311.02). Clearly, an audit client’s “environment”

includes its industry and major changes that industry is undergoing. The overall health of a client's

industry has important implications for the financial health of that company. Likewise, the changes

that an industry is undergoing have implications for the future of each company within that industry.

For these reasons, auditors must be cognizant of, and explicitly consider, industry-related factors in

planning audits.

4. Lowballing" refers to a method used by accounting firms to obtain audit clients, principally in a

competitive bidding process. When an audit firm lowballs, it offers to provide an independent audit

to a prospective client at an annual fee that is considerably below what other audit firms would

charge to provide that audit. In many cases, audit firms that lowball to obtain an audit client hope to

5. Different auditors would respond in different ways to this scenario. Probably the most common

response, and many would argue the most appropriate, would be to significantly expand the year-end

6. This is an important issue that the accounting profession has debated extensively in recent years.

Many critics of the profession have suggested that the integrity of an independent audit is

Case 1.8 Crazy Eddie, Inc.

65

personal relationships between the former auditor and his or her former colleagues within the given

audit firm. For example, on subsequent audits, the auditors may place too much trust in their former

colleague and thus overlook or discount potential problems in the client's financial statements.